A look at British movie magazines of 1975, in particular the adverts that nail their release dates. These magazines are still available secondhand on eBay. (These are all handheld photos from magazines no longer in publication - please don't scan books or magazines that are still in print...)

Joan Collins seemed to spend the whole decade in bed, in sex comedies (like this sequel to Alfie), and sex dramas (The Stud and The Bitch). I blame her sister...

|

| Films and Filming, January |

The whole year is dominated by big budget disaster movies. I blame Irwin Allen.

There were three Airport sequels in the 1970s, but it was Airport 1975 that fuelled half of the jokes in Airplane! The other half were inspired by Zero Hour (1957) that starred Dana Andrews, who also appeared in Airport 1975! English author Arthur Hailey started it all by writing both the script for Zero Hour and the original Airport (1970) novel.

Amusingly, Airport 1975 was released in 1974...

Much more about Airport 1975 here.

|

| Photoplay Film Magazine, January |

Disney films were the most obvious to drag children to see, though I was often disappointed by just how 'kiddie' they were. Here's a great exception, a Jules Verne-type adventure with no children in the cast. A lost island thrown back to Viking times, volcanoes and some amazing killer whales...

More about The Island at the Top of the World here...

|

| Photoplay Film Magazine, January |

Sorry that I'm mentioning movies here that were actually released the year before, but I'm sticking to the publication 'dates' (the month printed on the magazine cover) in order to stay sane. The Man with the Golden Gun was another big Christmas movie that opened in December 1974.

|

| Film Review, February |

Rising megastar James Caan and Alan Arkin in an early 'buddy cop' movie, mixing action, comedy and edgy, violent 'rogue cop' rough justice. Director Richard Rush later made cult favourite, The Stuntman, about a megalomaniac film director.

Looking at this year's clippings, a couple of films are mentioned almost throughout the year. Some films would get pre-publicity to raise awareness (easy to do because they'd already been released in America). In the case of Earthquake, cinemas would also have had to wait for the limited number of Sensurround speakers to be heaved around the country.

|

| Film Review, April |

Can't find an exact date when Earthquake first opened in Britain, but it could have been as early as January (when Films and Filming did their photo-preview). Seems rather late that Film Review gave it this splashy article in April.

|

| Surrey Comet, August |

Even later, Earthquake is only hitting Outer London eight months after the premiere. The giant, sub-base frequency Sensurround speakers caused problems in multi-screen cinemas, as the vibrations would leak into other theatres.

|

| Film Review, April |

Onto Easter, the first of a series of lavish Agatha Christie adaptions throws their best of British cast at even the smallest roles.

|

Amicus Films finally admit to making children's films besides horror. Even so, there's giant monsters and a high body count in this first of three Edgar Rice Borough novels, adapted by genre fan and producer Milton Subotsky.

This issue of Film Review could barely believe the number of disaster movies opening in the coming year. But The Towering Inferno was the most spectacular of them all. It's popularity even saved lives, as high-rise buildings were forced to reinforce and improve their fire safety standards.

|

|

|

| Film Review, April |

Even though it premiered in London in January (at the Warner West End), it was still playing in five West End cinemas three months later. It would run for several weeks in our local ABC and make several re-release return visits too.

More about The Towering Inferno here.

|

| Film Review, April |

The original version of The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3 was based on a bestselling novel. It must have been popular because it repeatedly played through the rest of the decade, if you wanted to make a quality thriller double-bill.

More about The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3 here.

One of my favourite issues of Films and Filming, April 1975, somehow contains photo-features for four of my fondest movie-going experiences.

|

| Films and Filming, April |

The Rocky Horror Picture Show gets five full pages of photographs. I think they liked it.

|

| Films and Filming, April |

Flesh Gordon has to be seen to be believed. Starting life as hardcore pornography, Flesh was funnier and sexier than the huge budgeted official adaption that eventually arrived in 1980.

|

| Films and Filming, April |

I saw Brian De Palma's Phantom of the Paradise on a double-bill with Rocky Horror. They might even have been released together as a double-bill. With songs by Paul Williams, before he did Bugsy Malone and The Muppet Movie, starring Jessica Harper before she made Suspiria, Phantom references practically every horror movie that had gone before.

More about Phantom of the Paradise here. |

| Films and Filming, April |

Finally, the April issue of Films and Filming also previewed Mel Brooks' Young Frankenstein. |

| Photoplay, May |

This photo, published in Photoplay Film Magazine, appears to be a scene missing from Young Frankenstein. |

| Film Review, July |

Young Frankenstein was unusual for being shot in black-and-white, as a homage to the Universal horror films of the 1930s. This made publicity photos published in colour rather a revelation. Here's Teri Garr, before she appeared in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Mel Brooks would again be scrabbling for increasingly rare black-and-white film stock when he produced The Elephant Man with David Lynch

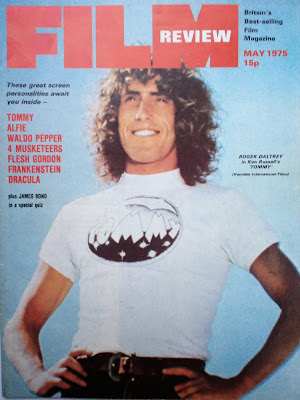

Another example of early publicity. Roger Daltrey on the cover for Ken Russell's Tommy, months before the cinema release.

|

| Film Review, November |

An early example of a film released with stereo sound, though only in a few cinemas. I don't remember hearing stereo in a cinema before Star Wars in 1977.

Much more about Tommy here.

|

| Photoplay, May |

Director Sam Peckinpah dominated the decade. His name on a poster almost outweighed the cast - guaranteeing the toughest of tough, violent thrillers. But his drinking problem meant that he was a liability to insure for U.S. productions, and he'd often have to make his films in other countries instead. Bring Me The Head of Alfredo Garcia was shot in Mexico, for instance.

|

| Film Review, June |

Monty Python's first original feature film, directed by the two Terrys, Gilliam and Jones, remains my favourite. I'd missed most of their TV shows because I was too young. The films were my first taste of Python. And I liked it.

|

| Film Review, August |

First written in the 1930s, the 1970s saw the start of Doc Savage's (200) pulp adventures being reprinted with all new cover art. Classic sci-fi producer George Pal bought the rights to ALL the novels and expected to start a franchise. He blamed studio interference for its failure, when they recut and redubbed the film. A shame, because Ron Ely was the perfect choice to play Doc.

Norman Jewison's Rollerball first appeared on the cover of Photoplay magazine in 1974. A year later, and six months before the UK release, here it is again on the front page.

|

| Films Illustrated, September |

Whether it ran into production problems (I've read about clashes between James Caan and the director) or whether the release was delayed because of worries about the violent content, I don't know. |

| Film Review, November |

Another crowd-pleasing film that wouldn't stay away, Bob Clark's Black Christmas gave us an early taste of slasher movies before the phrase had been invented. I caught it a couple of times when it was later re-released in double-bills. This was the British debut.

Previous magazine flashbacks...

Lawrence of Arabia and more from 1963

Blow Up, The Trip and more from 1967

Barbarella, Witchfinder General and more from 1968

Rosemary's Baby, When Dinosaurs Ruled The Earth, Women In Love and more from 1969

M*A*S*H, Myra Breckinridge and more from 1970

The Devils, Deep End, double-bills and more from 1971